Bound for Nostalgia, Demons, and Lonely Hearts: An Ultra Fan’s Guide to Obayashi Nobuhiko

Bound for Nostalgia, Demons, and Lonely Hearts: An Ultra Fan’s Guide to Obayashi Nobuhiko

Disclaimer: Information concerning sources and images used can be found in the concluding section of the article. The Author's Endnote section explains how the writer managed to see the discussed movies. To avoid formatting issues, there are no captions under screenshots of movies in the main body of the text. Should you wish to know the name of a film on the basis of a picture, please click on it, and it will send you to the appropriate site. Information about image attribution can also be found at the end of the text. This article was prepared in accordance with the 2023 MDL guidelines and can be viewed in light mode and dark mode. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author.

Do I imagine the scenes play out in my head while I write? Of course. In fact, for me, that is one of the joys of writing fiction — I’m making my own film made just for myself. ~ Haruki Murakami, 2021 (source)

In the abyss of the internet, there are many memetic representations of the pop-cultural phrase “This is what happens when an unstoppable force meets an immovable object,” but in my opinion, the best example depicting this phenomenon (especially in the literally realm) are two words: Haruki and Murakami. In essence, one cannot exist without the other.

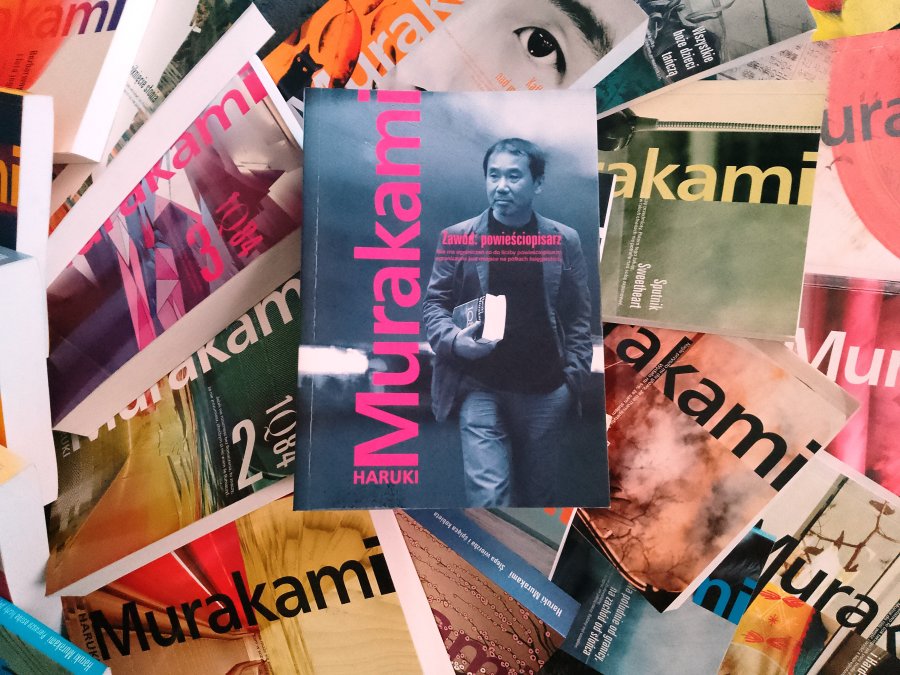

Indeed, Haruki Murakami is one of the few Japanese writers whose books are being read and cherished by fans across the globe. Since his debut in 1979, he has continued to enchant readers with his unique writing style, which blurs the line between real and unreal, happiness and loneliness, love and longing. What is more, he is able to describe mundane everyday activities in the most abstract way with the usage of magical realism.

My first encounter with Murakami happened around 2009 when I read Kafka on the Shore (2002). It was undoubtedly a very complex, one-of-a-kind reading experience which encouraged me to familiarise myself with more of Murakami’s works. Little did I know in a matter of a year, I joined the league of devoted fans.

|  |

Nevertheless, a lot of stuff had happened in my personal life at that time which led me to change my perspective on Murakami. It became a love-and-hate relationship because while I adored the slice-of-life pieces by the author, I just could not handle the way he treated female characters in his novels. As time went by, my fan frenzy gradually wore off, and I accepted the premiere of Killing Commendatore (2017) without even batting an eye.

However, come the year 2022 and Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s Drive My Car arrived in cinemas worldwide, jamming on the brakes. As I wrote in my original blog post, I could not miss the opportunity, and I saw the film at a film festival in my country. To be honest, my initial response to it was not very enthusiastic. I felt that there was something off, something was missing. This feeling of emptiness reinvigorated my interest in Haruki Murakami and became the foundation for this editorial: an exploration of the many movie adaptations of Murakami’s works. Dear MDL-ers, without further ado, let’s dive into the heart of the matter.

Hear the Wind Sing (1981) |

One would think that it was not until the mid-2000s that filmmakers took an interest in adapting Murakami, but the first attempts were made as early as the early 1980s. From the get-go, young Murakami was very adamant about the prospect of not adapting his novels and short stories, and he emphasised this statement in an interview with the New York Times in 1990 (source). However, the writer did give his permission to young director Kazuki Omori to translate his debut novel Hear the Wind Sing to the silver screen.

To be honest, I found it genuinely surprising that the first adaptation of Murakami is based on his very first book. In Novelist as a Vocation (2017), Murakami describes in detail how he worked on the novel and provides even more background in The Paris Review interview from 2004, but he never mentions Kazuki Omori’s motion picture.

This may stem from the reason that, allegedly, Murakami is not particularly pleased with how the movie turned out to be. In fact, the writer does not seem to be satisfied with his first novel at all, calling it a deconstruction of the traditional Japanese novel: "I wanted to write something, but I didn’t know how. I didn’t know how to write in Japanese—I’d read almost nothing of the works of Japanese writers—so I borrowed the style, structure, and everything, from the books I had read—American books or Western books. As a result, I made my own original style" (source).

|  |

From my point of view as a reader, I found it challenging to read Hear the Wind Sing. Indeed, this is not the Murakami we all know and love, but a young writer who tries to find his voice in the literary world. The novel itself focuses on an unnamed narrator who recalls the summer of 1970. He was a student at a university in Tokyo back then and returned to his seaside hometown in Kobe for vacation. The whole story (albeit relatively short) feels disjointed, filled with many interruptions and multiple points of view. If anything, in terms of its postmodernist structure, it appears to be a spiritual companion piece to Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman.

It is interesting that director Kazuki Omori tried as hard as possible to reflect the postmodern style of the novel in his movie. Nevertheless, the adaptation, while desperately trying to be innovative and unconventional, turns out to be extremely dated and formulaic (often omitting crucial themes of the novel altogether). Omori clearly tried to tap into the Japanese New Wave trend initiated by Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes (1964) and perfected by Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House (1977) and Yoshimitsu Morita’s The Family Game (1983).

Nevertheless, Omori is not any of these filmmakers. His take on Hear the Wind Sing was obviously crafted with care and faithfulness, but at the same time, it is uninviting and pretentious. Nevertheless, I have to praise the director’s attempt to play with POV shots of the main hero as he recollects his experiences.

It also has to be noted that Haruki Murakami rarely allowed for the release of his first two novels, Hear the Wind Sing and Pinball 1973, outside of Japan. He regards Wild Sheep Chase (1989) as the true beginning of his writing style.

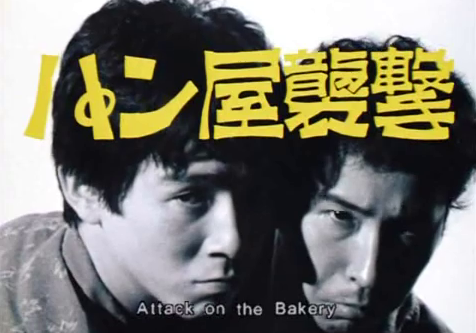

Attack on a Bakery (1982) |

Although Murakami was uninspired and discouraged by Omori’s approach to the delicate source material, he did allow an indie filmmaker Naoto Yamakawa to translate two of his short stories into film. The first of which was Attack on a Bakery.

The original story is told in a very straightforward manner. Two guys want to rob a bakery but end up getting tricked by the owner into listening to Wagner music. The aftermath is ambiguous and remains as such in the sequel story. It appears as if the protagonists were cursed, and they started to feel hunger for something more than just food. If anything, this story shows that Murakami used to be more freewheeling in the early days of his writing.

The short film itself is a faithful representation of the original story, even to such an extent that director Yamakawa takes and repeats passages from the story verbatim, even going so far as to include the narration of the main hero.

The director also skillfully plays with the usage of colour and POV of the main characters. Even though it is an indie endeavour made with guerilla filmmaking means (no studio ADR, just audio recorded on location) the cinematography really plays an important part in the film. The adaptation accurately reflects Murakami’s angst about the value of culture and the illusion of politics in Japan in the 1980s. The narration in the adaptation actually feels a bit more refined than in the original short story.

|  |

Coincidentally, there was another adaptation of the short story. The South Korean production directed by Yoo Sang Hun Acoustic from 2010 is an omnibus film which consists of three separate stories. The middle section of the film is heavily inspired by Murakami’s Attack on a Bakery, but certain creative liberties were taken in this instance.

The main heroes are not some shady assailants who carry out the robbery due to hunger. They are aspiring musicians who accidentally leave the guitar they want to sell at a bakery store. When they come back to retrieve the instrument, the owner of the bakery turns out to be an experienced musician who gives them pro tips and inspires them to chase their dreams.

It is a fairly light-hearted Murakami-inspired short, but it does not feel cinematic at all. In fact, Acoustic was shot with the usage of a digital camera only. As a result, the movie feels more direct and has this distinct TV drama quality that makes you instantly engaged.

A Girl, She is 100% (1983) |

Similarly, as in the case of Attack on a Bakery, director Yamakawa together with screenwriter Chikako Nakagawa remain faithful to the original source material: the story called On Seeing the 100% Perfect Girl One Beautiful April Morning. Apart from repeating dialogue and narration from the story, Yamakawa shot the whole thing in black and white and colour with an expert usage of the stop motion technique and changing the frame rate of the picture.

As a result, we get an insightful representation of Murakami’s original vision; that is to say, love works in mysterious ways, and you need to grab it when you feel it because otherwise, the passage of time will destroy your chance for happiness. Still again, although we may meet a perfect girl or a perfect man, they will most likely walk past us without noticing us.

I dare to say that Yamakawa managed to improve the original story by reworking the opening of his movie and adding a line which was not present in Murakami’s story: “I met a girl in Harajuku who was 100% of me”. It should be noted as a fun fact that A Girl, She is 100% and Attack on a Bakery feature the wonderful actress Shigeru Muroi at the beginning of her acting career. In addition, the two films were translated into English by the late film expert Donald Richie.

In the year 2008, there was another adaptation of the short story done by director Tom Flint, but I was unable to find it, apart from scarce information on an abandoned movie festival site (source).

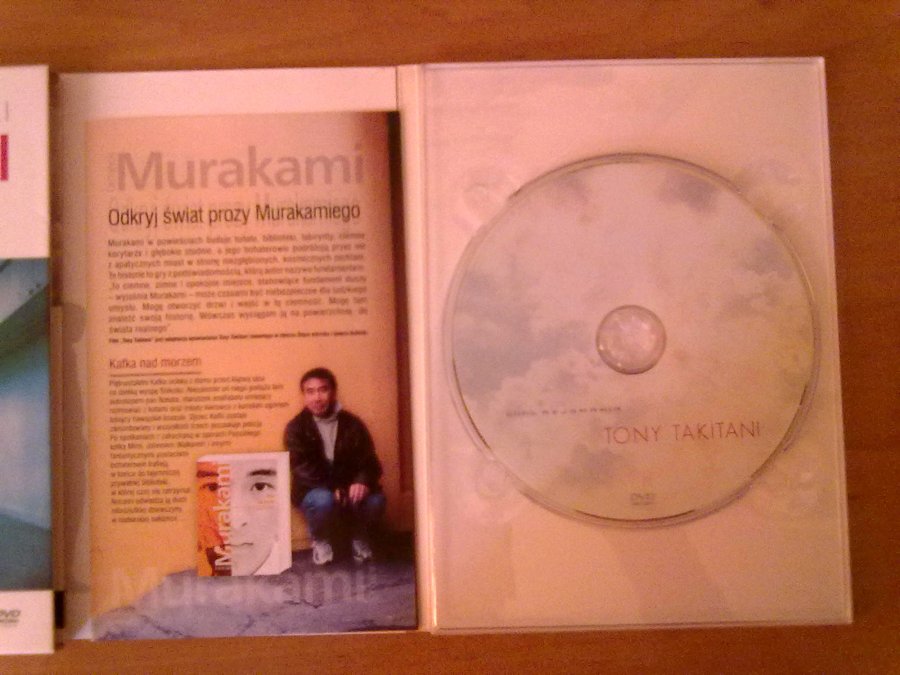

Tony Takitani (2004) |

I have to admit that Tony Takitani was the first ever movie adaptation of Murakami I have ever seen. Upon seeing Jun Ichikawa’s movie for the first time, I was utterly swept away by its ethereal ambience, hypnotic left-to-right camera work, Hidetoshi Nishijima’s restrained narration, Ryuichi Sakamoto’s music score, and outstanding performances by Issey Ogata and Rie Miyazawa. It is truly a touching film about love, devotion, and loneliness, about a man who was emotionally alone and became such for the rest of his life.

From today’s perspective, I would have appreciated the film more had it been more conventional in its execution. Do not get me wrong, director Ichikawa did a perfect job in trying to visually recreate the sense of loss and suffering so vividly present in Murakami’s works, but a lot of stuff from the original story got lost in translation. Ultimately, I would have loved to see a movie adaptation that is centered not only on Tony Takitani but on his father as well. In addition, if you suffer from inner ear problems, the cinematography in this film may exacerbate your symptoms.

All God’s Children Can Dance (2008) |

As a reader, I have always had issues with the All God’s Children Dance story. It never managed to fully grasp my attention because of the lacklustre conclusion. I have always regarded this tale as Murakami’s hot take on the issues of fatherhood, unrequited love, and religious devotion. What makes us children of God? What is our real identity? How do we relate to our parents? What shapes our personality? Murakami suggests that in union with nature, we can achieve peace of mind.

Sadly, director Robert Logevall chose to mainly focus on the NSFW undertones of the original source material, which were only subtly touched upon by Murakami. The end result is a movie that feels disjointed. While it has some poignant segments and beautifully shot LA locations, it seems most of the time that the director did not have a solid idea as to how to carry the storyline beyond the adult content. Rewatching this movie 15 years after it came out made me all the more sorry for performers Joan Chen and Tzi Ma, whose talents were wasted in this forgotten-by-time production.

The Second Bakery Attack (2010) |

The Second Bakery Attack is a sequel to Attack on a Bakery and was originally published in the August 1985 issue of Marie Claire Japan. It sees the return of the main hero, who (this time with his wife) attempts to lift off a curse from the first story by robbing a new bakery. It is not a story about hunger, poverty, or class struggle, but a funny tale about the peculiarities of the marriage lifestyle told very much in the Satoshi Miki style.

This short story has actually (so far) three(!) movie adaptations. Unfortunately, I could not track down the official 2010 Mexican-American version, directed by Carlos Cuarón, with Kirsten Dunst and Brian Geraghty in the leading roles.

However, there is an independent short film made for the New York Film Academy by director Zhu Zhen Zhong. It was uploaded on YouTube by actor Christopher Sanchez who plays the protagonist in the film. As in the case of Naoto Yamakawa films, this is also a faithful adaptation of the original short story. However, there is no overarching narration, and the main plotline difference is that the couple decides to rob a pizzeria rather than McDonald’s. Also, the dynamic between the couple is different. In the story, the wife leads the charge because she wants to get rid of the curse, but in this adaptation, she seems to be enjoying the whole robbing affair. It is a nicely done indie adaptation in the New York setting, but the cinematography is, unfortunately, uninspiring.

There was also a Chinese production done entirely in the Mandarin language. It is obvious that the producers had more resources to work on because this short film is definitely more cinematic and lavish in terms of framing and camera set-ups, but nevertheless, I still prefer Zhu Zhen Zhong’s minimalist approach.

Norwegian Wood (2010) |

I have to be honest, so let me say that the novel Norwegian Wood (1987) never won me over. I always regarded it as a standard romance story in which a guy is torn between choosing two girls. Murakami himself admitted that he set out to write the novel in order to prove to himself that he could write a truly realistic story without the aid of magical realism (source). In addition, it was also a strategic move to widen his reading audience (source).

Judging from the immense popularity of Norwegian Wood, which overwhelmed Murakami and made him move out of Japan, I am surprised that there was no movie adaptation immediately after the book’s release. Perhaps this stems from the fact that Japanese Cinema was concerned with other sensibilities towards the end of the 1980s, so there was no room for yet another sappy simp fest set amidst the historical backdrop of student protests of the 1960s.

|  |

Well, in 2010, a Vietnamese-born French film director and screenwriter, Tran Anh Hung, finally adapted Murakami’s all-time popular novel to the film. In my opinion, this was not a successful attempt.

If there is anything positive I can say about the movie, it is that I applaud the beautiful production design and stunning outdoor locations. Storywise, unfortunately, the film fails to deliver the magic of Murakami. Instead of focusing on the internal feelings of the protagonists, the adaptation revels in NSFW content, cranking it up to the max.

As in the case of Hear the Wind Sing, knowledge of the original novel is very much required to appreciate what is going on in the film. However, director Kazuki Omori at least had a stylistically-charged vision in accordance with which he crafted his movie. With regard to Norwegian Wood, however, there is no directorial vision, only good-looking scenes. This, to my mind, makes Norwegian Wood the weakest Murakami adaptation out there.

Burning (2018) |

If you are looking for a slow-burn (pun very much intended) psychological thriller filled with symbolism and soothing visuals, then you can’t go wrong with Lee Chang Dong’s Burning, which is an adaptation of Murakami’s Barn Burning short story. The original tale provides an idiosyncratic look at the relationship between three completely different people: a writer, a free-spirited woman, and her businessman boyfriend. I regard the main hero as a person who is actually out of touch with the youth; that is why he is unable to tap into their sensitivity, even though he tries as hard as possible to get in touch with the girl who eventually goes missing and catch a glimpse of a barn on fire (even though it was already burnt).

Lee Chang Dong’s production appropriates the narrative structure from the original story but also fills it with motives from Willaim Faulkner’s own Barn Burning story (1939) and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby novel (1925). In consequence, the movie becomes “a story about young people in today’s world”, as explained by the director. Burning explores not only the issue of class difference but also emotional incontinence, dependency, and jealousy. I would go so far as to say that, with his performance, Yoo Ah In singlehandedly carries the weight of the film on his shoulders.

Murakami praised the film and made the following comment upon seeing it: “By changing the setting from Japan to South Korea, it felt like a new mysterious reality was born. I want to highly commend these kinds of ‘gaps’ or differences” (source).

Hanalei Bay (2018) |

Hanalei Bay is that “other” Murakami production from 2018 which did not manage to gain as much international recognition as Burning. Personally, I believe more people should watch this indie film.

The original story focused on a mother who lost her son because of a shark attack in Hawaii. One could think that Murakami purposely came up with such a theme to tell a sappy tale centered on grieving, but the mother figure is an extremely bitter and self-reliant person who helps out two noob teenagers from Japan.

Director Daishi Matsunaga recreates the main plot points to a T, but the reserved camerawork, stoic atmosphere, and the striking performance by the legendary Yoh Yoshida are the factors that make this particular adaptation stand out to me. The third act is especially captivating as the viewers see a clear difference between the difficult past of the main heroine and the present stillness of the titular bay.

I have to say that the mother in the film is not simply bitter. She processes her feelings towards her unruly late son while becoming the mother figure to two Japanese surfers. Undoubtedly, the most touching scene is the one in a skate park, and it is an original addition not penned by Murakami at all.

Drive My Car (2021) |

Undoubtedly, Ryusuke Hamaguchi's adaptation of Murakami's tale from Men Without Women (2014) short story collection took the cinematic realm by storm, gaining numerous awards, including an Oscar for Best International Feature Picture of 2022. As I wrote already with regard to this particular movie, my opinion of Drive My Car goes against the general consensus.

I do not want this subsection to turn into backtracking from my original reaction, so allow me to say that I embarked on a quest to understand why I have issues with this overwhelmingly popular movie. Certainly, it is a visual feast filled with wonderful cinematography, amazing performances, and layers of intertextuality. However, I strongly believe that the Drive My Car movie is a perfect example of an anti-Murakami adaptation.

That is to say, I found it hard to relate to the emotional dilemma of Yusuke Kafuku, the main protagonist. After having read numerous novels and stories by Murakami, I was under the impression (or rather I felt conditioned by Murakami to expect) that Kafuku's journey to Hiroshima will also be (symbolically) his own introspective bildungsroman: his voyage to come to terms with the loss of wife. In a way, the film delivered this resolution, but the culminating point was not charged with positivity and hopefulness but rather with trauma. Director Hamaguchi explained that "Murakami’s writing is wonderful at expressing inner emotions, and I think that’s why people want to adapt them. But it’s really difficult to re-create those inner feelings in film" (source).

|  |

A great deal of help in my attempt to deconstruct the film came from two video reviews: the first presented by the Criterion collector Daisuke Beppu and the second done by Polish film critic Tomasz Raczek. On the basis of these reviews, I was able to understand that Drive My Car is not a movie for everybody. It was tailored for people who are at a specific stage in their lives, and they have to invest their emotional baggage to be able to fully experience the cathartic journey of Yusuke Kafuku. Drive My Car is not a conventional bildungsroman, it is actually very far from that. Director Hamaguchi purposely drifts away from Murakami's writing convention for the sake of telling the story not just about loss and isolation, but about communication (or lack thereof) between the hero and other people, and the imprint they leave on his life.

Consequently, this out-of-the-box approach is what makes Drive My Car a unique viewing experience, and it certainly made me appreciate the film more while rewatching it for the purposes of this article. It comes as no surprise that Haruki Murakami himself gave this movie his personal seal of approval, but he felt a bit disappointed when he saw on the screen that the original version of the Saab 900 he envisioned was modified (source). Nevertheless, the writer stated about the film, “I was drawn in from beginning to end. I think that this alone is a wonderful feat” (source).

Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman (2022) |

Last but not least, it has to be mentioned that the first-ever animation of Murakami’s writings (mainly inspired by such short story collections as After the Quake, The Elephant Vanishes, and Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman) is currently making rounds in cinemas worldwide. It is an international co-production written, produced, directed and composed by Pierre Földes. Personally, I commend such an artistic endeavour because I have always felt that many of Murakami’s novels and stories would constitute perfect material for animation because this domain allows more leeway for the implementation of magical realism than standard film riddled with CGI. I have not yet seen the film, but I hope I will be able to do so in a couple of months when it finally premieres in my country.

Conclusion |

All things considered, when it comes to the adaptations of Haruki Murakami, there is always a great selection that will suit everybody's taste. Murakami himself admitted that he prefers it when the filmmakers use his works only as a source of inspiration because that allows the adaptations to depart and seek their own unique identity: “When my work is adapted, my wish is for the plot and dialogue to be changed freely. There is a big difference between the way a piece of literature develops and how a film develops” (source).

That is why Murakami likes such movies as Burning and Drive My Car for the reason that these motion pictures try to interact and play with his literary creations instead of recreating them word for word, image for image.

Personally, I find myself more in the camp of “faithful adaptations” because I can’t help but appreciate and relate to the ambience of A Girl, She is 100%, Attack on a Bakery, and Hanalei Bay. What is more, I am genuinely convinced that Murakami’s non-fiction books are excellent material for future adaptations. I would love to see Underground (1997), What I Talk About When I Talk About Running (2007), and Abandoning a Cat: Memories of my Father (2020) turned into movies.

To conclude, I believe this article should have been given the title A Gentle Loner, He is 100%; or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Appreciate Haruki Murakami, but I think this would have been too controversial and misleading for the readers. The original aim of this article was to explore the many adaptations of the author’s works, but in the process of doing so, I also found myself exploring my own feelings towards the writing style of Haruki Murakami. As a 30-year-old man, being in the standard age of Murakami’s heroes and with enough emotional baggage at hand, I came to appreciate the writings of this man much more. Even though I still disagree with the way he treats women in many of his novels, I appreciate his delicacy, gentleness, and poetic side, which allows him to present and evaluate a wide array of human feelings with ease and finesse.

It has been proven that Haruki Murakami did visit my homeland back in 2019, but it was not an official tour. He just stopped by to hang around and wrote an article based on his experiences for a travel magazine (source). Unfortunately, nobody recognised him in the wild (He visited Warsaw and Kraków). Well, if I were to have a chance to meet him while crossing a street in Poland, I would not dare to come up to him and invade his personal space, but… I would think to myself, "He is a gentle loner. He is 100% of his readers."

Epilogue |

All in all, I remembered that in his non-fiction work Novelist as a Vocation (2017), Murakami delves into the issue as to why he had not received the prestigious Akutagawa Award, even though he was shortlisted on two occasions. Murakami explains that such ponderings should be left behind, and he does not care about winning or not winning any literary award (Murakami 2017: 54). Honestly, I could not agree more with him. In my opinion, not receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature in modern times is a greater privilege for a popular author than receiving one. My reasoning is that even though the literary elite constantly desires to have Murakami within their ranks, the author manages to elude this type of harmful categorisation time and time again by not chasing after the awards*, but by creating engaging stories, which are being read and experienced by people around the world. As always, allow me to end the article with the artist’s own words:

I want my readers to laugh sometimes. Many readers in Japan read my books on the train while commuting. The average salaryman spends two hours a day commuting and he spends those hours reading. That’s why my big books are printed in two volumes: They would be too heavy in one. Some people write me letters, complaining that they laugh when they read my books on the train! It’s very embarrassing for them. Those are the letters I like most. I know they are laughing, reading my books; that’s good. I like to make people laugh every ten pages (source: Art of Fiction).

Closing remark: The title of the article was inspired by Haruki Murakami’s Colourless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage (2013), much in the same vein as What I Talk About When I Talk About Running was inspired by Raymond Carver's collection of short stories entitled What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981).

*Endnote: Murakami actually withdrew his name from the Nobel Prize shortlist in 2018, saying that he feels gratitude for the nomination, but he wishes to “concentrate on writing, away from the media attention” (source).

The Authors’s Endnote: For the purposes of this article, I have tried to watch the discussed movies as legally as possible. The short films are available on YouTube. I watched Tony Takitani on DVD from the Azjamania distribution label. Similarly, I saw All the God’s Children Can Dance on DVD from Monolith Films and Norwegian Wood on DVD from Thunderbird Releasing. I watched Hanalei Bay and Burning at a local film festival in 2019. I have also rewatched Burning recently on DVD from Aurora Films. I rewatched Drive My Car via Polish VOD service. Burning and Drive My Car are available on numerous streaming services internationally. Drive My Car can also be watched on Blu-Ray and DVD from the Criterion Collection. Unfortunately, Hear the Wind Sing is not officially available outside of Japan. Release information about Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman animation can be found on the Zeitgeist Films site.

Images used: The featured images, as well as images used in the introduction and the epilogue image, were taken by @Ebisuno92 for MDL only (Copying the image without permission of the author and MDL admin staff is prohibited) * Haruki Murakami photograph was issued by Wikipedia under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, which allows to copy, distribute and transmit the work * Drive My Car promotional image belongs to Bitters End * The Second Bakery Attack drawing was created by Kinuko Y. Craft and used for the January 1992 issue of Playboy * Remaining photos are screenshots taken from the movies.

Sources: Haruki Murakami Interview: The Art of Fiction No. 182 (The Paris Review) * Haruki Murakami and the Challenge of Adapting His Tales for Film (NY Times) * Letter from Tokyo: Brando, the Stones and Banana Yoshimoto (NY Times) * Con-Can Movie Festival * Murakami Withdrew Name From Alternative Nobel Prize for Literature (The Bookish Elf) * What Did Haruki Murakami Write About Poland? (Youtube) * Drive My Car Review (Daisuke Beppu) * Drive My Car Review (Tomasz Raczek) * Novelist as a Vocation (2017) by Haruki Murakami (Polish edition by Muza SA) *

Ebisuno92’s Previous Articles: * Bound for Nostalgia, Demons, and Lonely Hearts: An Ultra Fan's Guide to Obayashi Nobuhiko * Pitching Ghostbusters as a J-Drama * A Tribute to Sonny Chiba (with Old_Anime_Lady) * If The Woman Behind The Counter was a J-Drama * Underground Nightmares and Social Anxieties: Aum Shinrikyo on Film * For Comrade's Eyes Only: Interview with Johannes Schönherr (with Seonsaeng) * Takeshi Kitano Is Gearing Up to Direct His Final Film "Kubi" * From Zero to Hero: A Retrospective Guide to Yaguchi Shinobu (with Joe Shiren) * An Ultra Fan's Guide to Takeshi Kitano * An Ultra Fan's Guide to Kyoko Kagawa * Feel the Power of Office Ladies: Shomuni Retrospective * "Watashi, Shippai Shinai No De!”: Daimon Michiko as the Ultimate Doctor-Hero (with Reika Bleu) * "Come on over, Spiritual Phenomena!” TRICK, A Franchise Retrospective * From Best Korea with Love: An Introduction to North Korean Dramas & Movies (with Seonsaeng) * Cursed Cassettes, Countdowns, and Corpses: A SFW Guide to the Ring Series * Blast from the Past: Did Bayside Shakedown Destroy Japanese Cinema? * Weekend Recommendations: Father Knows Best * Godzilla's on the Loose: 65 Years of Kaiju Rampage * An Ultra Fan’s Guide to Yeoh Michelle * Blast from the Past: A Guide to “Girls with Guns” Genre * Weekend Recommendations: Old School Movies * Ebisuno92's Weekend Movie Picks *

Thank you for reading.

Big thanks to the editors for their hard work.

Edited by: YW (1st editor)