This review may contain spoilers

If I stay where I am, I don't know how much farther I'll fall

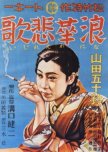

Osaka Elegy was a difficult film for me to rate. It attempted to reveal how men with money have power over women and even men with no money still exerted power over the women in their lives. Ayako, the female lead, did the wrong thing for the right reason in order to help the men in her life, only to suffer mightily for her selflessness.

Asai, the owner of a pharmaceutical company received no respect from his wife, nor did he give her any. He was verbally abusive of his female servants. At work he lusted after a young phone operator, Ayako. Initially, she rebuked his advances. She wanted to marry her noncommittal boyfriend and reached out to him for help. He was unable or unwilling to assist her family.

When her father was threatened with jail because of his embezzlement of 300 yen, she gave in and had an affair with Asai to pay off her father's debt. She would also pay off her brother's tuition. Neither man showed any gratitude, rebuffing her instead. Things went from bad to worse, eventually she was abandoned by all the men in her life showing her just how much their loyalty was worth.

Yamada Isuzu made a wonderful, conflicted heroine. She knew her father was inept and unkind, but still could not resist helping him by foregoing her dignity and reputation. Once ensconced as a mistress she began to forge her own limited power, a power dependent on the generosity of a more powerful man. Constantly rebelling against the label of a woman suffering from the "illness of delinquency" Ayako struggled to keep what dignity she could even when publicly humiliated. From shy telephone operator to a woman fiercely fighting for her future, from joy to utter despair, hopelessness to a tiny ray of hope, Yamada played out a wide array of emotions.

The film suffers from age, fading or blurry at times. Even with the shaky and blurred shots, there were many lovely and creative scenes. At times the camera gave the viewer distance literally and figuratively from the characters, at others it sat as a cold observer, intimately close to the destruction of trust and love.

Whether director Mizoguchi made this film as an indictment on the precarious situation of poor women or simply an observation of the women in the world around him, what played out was the price for not having power of one's own. Punishment awaited the woman stepping outside of conservative values even by the same unscrupulous people who turned her toward the dark to make their lives easier or more pleasurable.

Asai, the owner of a pharmaceutical company received no respect from his wife, nor did he give her any. He was verbally abusive of his female servants. At work he lusted after a young phone operator, Ayako. Initially, she rebuked his advances. She wanted to marry her noncommittal boyfriend and reached out to him for help. He was unable or unwilling to assist her family.

When her father was threatened with jail because of his embezzlement of 300 yen, she gave in and had an affair with Asai to pay off her father's debt. She would also pay off her brother's tuition. Neither man showed any gratitude, rebuffing her instead. Things went from bad to worse, eventually she was abandoned by all the men in her life showing her just how much their loyalty was worth.

Yamada Isuzu made a wonderful, conflicted heroine. She knew her father was inept and unkind, but still could not resist helping him by foregoing her dignity and reputation. Once ensconced as a mistress she began to forge her own limited power, a power dependent on the generosity of a more powerful man. Constantly rebelling against the label of a woman suffering from the "illness of delinquency" Ayako struggled to keep what dignity she could even when publicly humiliated. From shy telephone operator to a woman fiercely fighting for her future, from joy to utter despair, hopelessness to a tiny ray of hope, Yamada played out a wide array of emotions.

The film suffers from age, fading or blurry at times. Even with the shaky and blurred shots, there were many lovely and creative scenes. At times the camera gave the viewer distance literally and figuratively from the characters, at others it sat as a cold observer, intimately close to the destruction of trust and love.

Whether director Mizoguchi made this film as an indictment on the precarious situation of poor women or simply an observation of the women in the world around him, what played out was the price for not having power of one's own. Punishment awaited the woman stepping outside of conservative values even by the same unscrupulous people who turned her toward the dark to make their lives easier or more pleasurable.

Was this review helpful to you?

54

54 188

188 11

11